Autonomous vehicles are generally thought of as an alternative to mass transit and, therefore, as less relevant to cities like New York, where population density necessitates the use of mass transit. But maybe it’s time to rethink that.

Suppose you lived in this house at 73-6 69th Avenue in Queens:

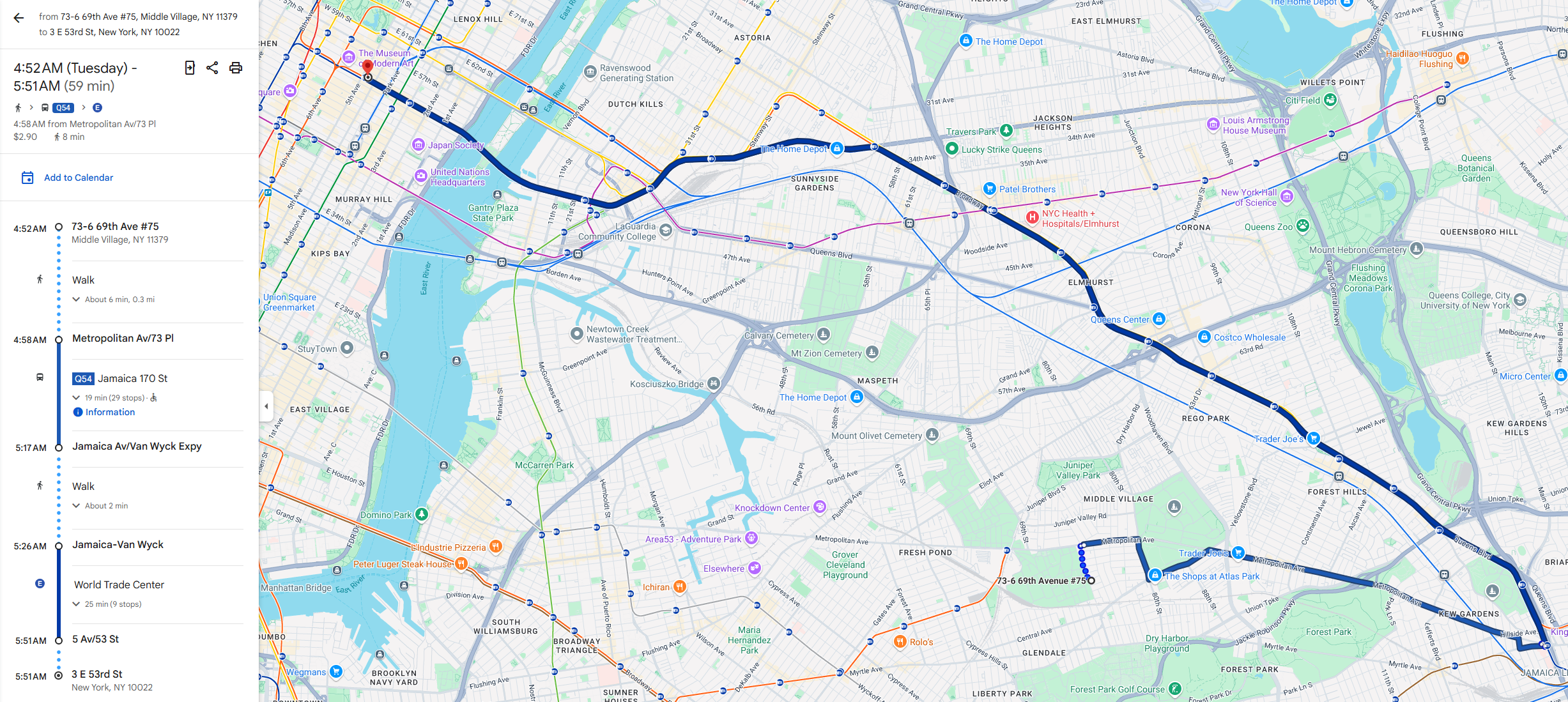

You work at 53rd Street and 5th Avenue, and you need to get there by 6:00 A.M., perhaps because you are a security guard or work the first shift at Starbucks. Unfortunately, your quickest commute via public transportation will take 59 minutes, most of which will be spent traveling by foot and then bus to get to the subway:

But let’s suppose that you were able to get to the nearest subway via a shared autonomous vehicle such as a Zoox:

At 5:20 A.M., a Zoox could get you to the Woodhaven subway stop in 10 minutes:

And the rest of your trip would take 21 minutes:

That adds up to 31 minutes, just over half the amount of time it would have taken if you’d taken a bus to the subway.

The conventional wisdom is that this solution would be more expensive, but that isn’t necessarily true. Buses are quite efficient if you need to take 40 people from location A to Location B. That’s why a bus from New York to Washington DC costs $40 on average, about 18 cents per mile. But when buses are carrying fewer passengers or are making many stops, they are less efficient. That’s why buses in New York City cost $6.68 per passenger which works out to about $3 per mile per passenger since the average bus trip is around 2.1 miles. (Bus fares are much less because most of the cost is covered by taxes.)

Now, let’s imagine that instead of spending that $6.68 on a bus, we instead spent it on sending you home in an autonomous vehicle. McKinsey has estimated that the cost of operating autonomous vehicles will fall to $1.30 per mile by 2035. That includes all of the hardware and software costs (which is only 30 cents per mile) as well as repairs, support and other costs.

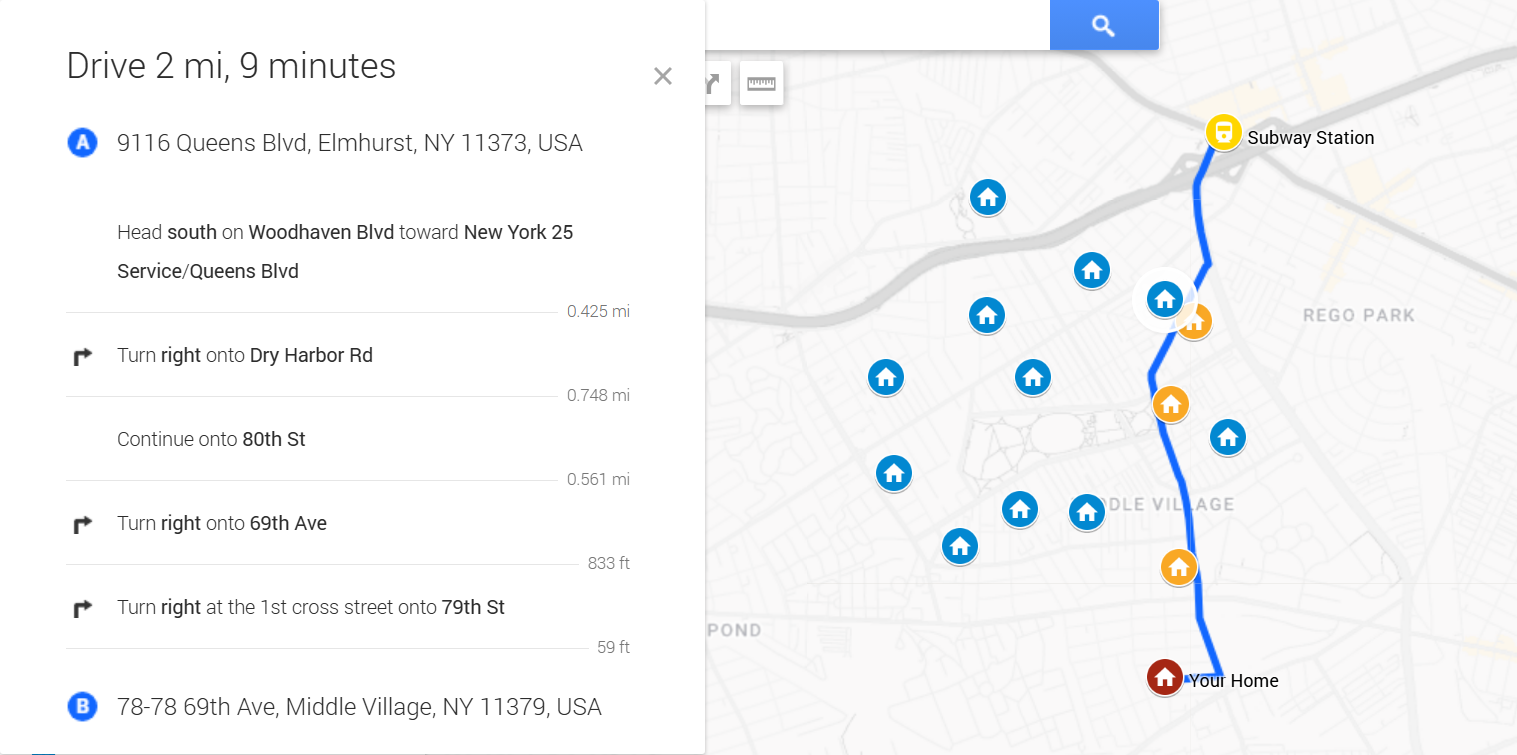

Now, let’s apply that to your commute from your home in Queens. You’ll notice that your trip from your home in Queens to the nearest subway stop is only 2.4 miles:

2.4 times $1.30 equals $3.12. Therefore, your ride would cost less than one-half of a typical MTA bus ride while being far more convenient.

Moreover, we haven’t taken into account shared rides. This is where things get quite interesting. The more people use shared autonomous vehicles (“SAVs”), the easier it will be to match them up without large route deviations. This is known as a “network effect.” One way to encourage SAV use it to incorporate it into mass transit. The Routing Company has designed software to do this.

Currently, ordering an Uber or Lyft to take you from a subway station to your home is inefficient. First, you have to go to the trouble of ordering it. Second, you either have to wait for it to arrive or accurately predict when you will arrive at the station and order it in advance. And third, you have to figure out which route would be most efficient, which may not be obvious. Perhaps the closest local subway stop is best but it may be faster to take an express subway to a stop slightly further away or another subway line or an express bus.

Now imagine that there is an app on your phone that did all that for you. You’re at work and you indicate on your phone that you want to go home. The app tells you what subway to take and where to get off and it monitors your progress as you head to your home. When you exit the subway, you find a small fleet of SAV’s has arrived to take you and your fellow subway riders home:

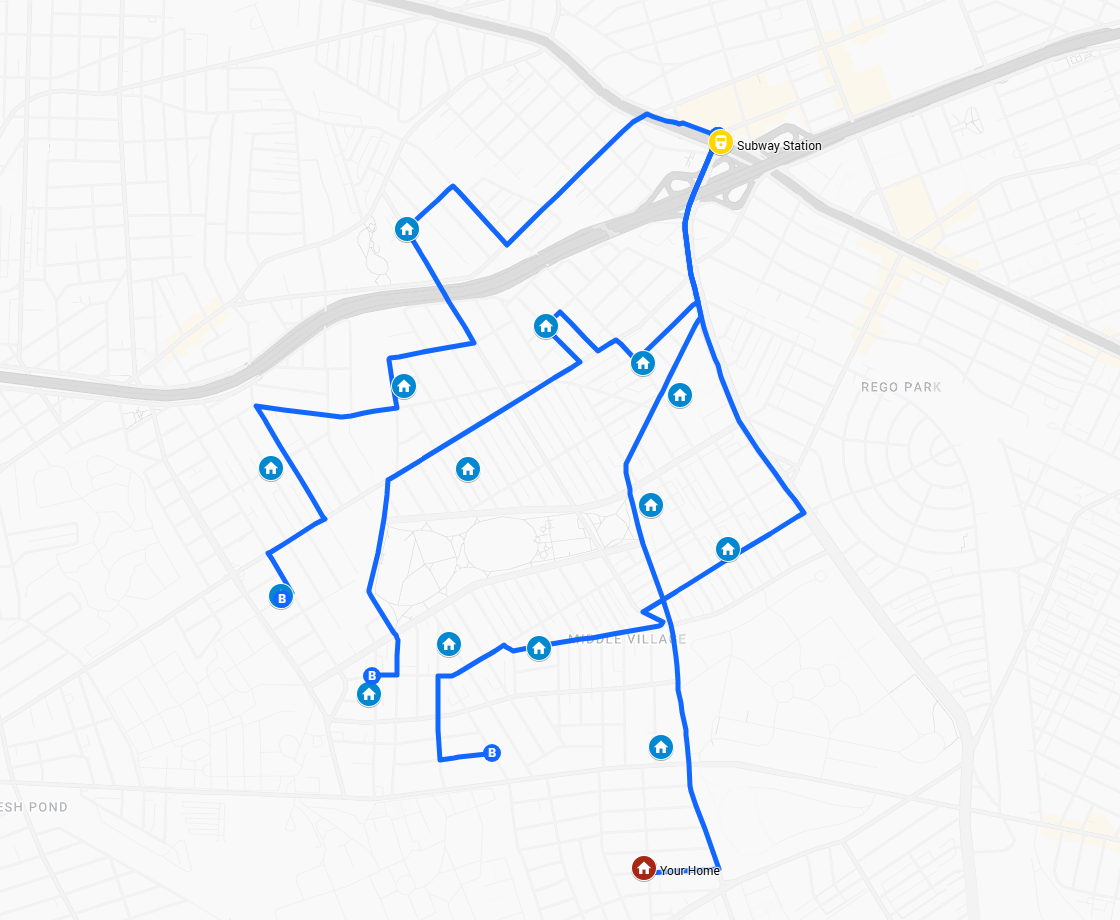

You would then check your phone to see the SAV to which you’ve been assigned. This is where network effects come into play. The more people use the SAV’s, the less each SAV has to deviate to take each passenger to their location. Let’s assume that we have 15 randomly distributed destinations to the southwest of the Woodhaven subway station including your home:

The challenge will be to get the passengers to these destinations in shared vehicles without taking long routes. Here is how these fifteen destinations could be served by four SAV’s:

Now, lets look at how long the route to your home will take:

Dropping off three passengers at the orange location along your route turns out to have no impact on the length of your ride. That’s in part due to the network effects of having sufficient density but it’s also the result of a small compromise that ride-sharing platforms make. Rather than dropping every passenger off at their exact location, rideshare vehicles drop passengers off at nearby locations that minimize deviations. If every passenger were dropped of at their doorstep, the length of your trip would balloon to 16 minutes, nearly twice as long:

To understand why, look at this portion of the map. To drop this person off at their doorstep requires circling the whole block since 79th Street is a one-way street:

By simply dropping this person at a nearby corner, the vehicle can avoid circling the block. Moreover, it will only take that person 2 minutes to walk home.

Now let’s return to cost. Assume that on average, a Zoox had two passengers at any one time. In that case, the per-mile cost for transporting passengers would fall to $0.65 and your 2.4 mile ride home would only cost $1.65, about a quarter of what it costs the MTA to provide bus trips.

Thus, making SAVs part of our transit system would save the MTA money and save commuters time. And it would also be good for everyone else. The more people take subways and commuter rails, the less congestion there will be. Not surprisingly, the lack of convenient mass transit in some neighborhoods is a major reason that people drive cars in New York City. Thus, by making it easier for people to access subways and commuter rails, we will diminish congestion throughout the city, particularly the critical arteries leading into Manhattan. So let’s stop thinking of autonomous vehicles and mass transit as enemies and start thinking of them as friends.